The defining example Gladwell presents is a longitudinal study which tracked violin students in Berlin’s elite Academy of Music. All of the students had begun the violin around age five, and all had evidenced exceptional skill; this was their ticket into the academy. The study asked the students about practice habits, and followed the students into their professional lives. What the researchers found was stunning. For the first few years, when all students were practicing at roughly equal intensity, there was little difference in their ability, but as time went on, the proficiency gap began to widen, and there was only one factor that correlated with proficiency—practice time. Here is an excerpt from Outliers discussing the ramifications of the study’s findings:

By the age of twenty, the elite performers had each totalled ten thousand hours of practice. By contrast, the merely good students had totalled eight thousand hours, and the future music teachers had totalled just over four thousand hours.

Ericsson and his colleagues then compared amateur pianists with professional pianists. The same pattern emerged. The amateurs never practiced more than about three hours a week over the course of their childhood, and by the age of twenty they had totalled two thousand hours of practice. The professionals, on the other hand, steadily increased their practice time every year, until by the age of twenty they, like the violinists, had reached ten thousand hours.

The striking thing about Ericsson’s study is that he and his colleagues couldn’t find any “naturals,” musicians who floated effortlessly to the top while practicing a fraction of the time their peers did. Nor could they find any “grinds,” people who worked harder than everyone else, yet just didn’t have what it takes to break the top ranks. Their research suggests that once a musician has enough ability to get into a top music school, the thing that distinguishes one performer from another is how hard he or she works. That’s it. And what’s more, the people at the very top don’t work harder or even much harder than everyone else. They work much, much harder.1One can see how such findings might be important for Shakespeare’s biographers, for the story of Shakespeare’s rise from rural glover’s son to the greatest writer in English history is frequently held up as an example of “genius”—nature—triumphing over environment. Shakespeare was a “natural” poet, who picked things up as he went along, absorbed what he could from books when he had the chance. His genius was so profound that his rise to poetic excellence was virtually pre-ordained at birth. This makes a great story, but is it credible?

Although Gladwell never mentions Shakespeare, what he has to say in Outliers gives us new insights into the conventional Shakespearean biography, for the truth uncovered about the violin students appears to be universal:

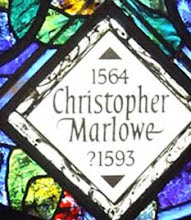

"The emerging picture from such studies is that ten thousand hours of practice is required to achieve the level of mastery associated with being a world-class expert—in anything,” writes the neurologist Daniel Levitin. “In study after study, of composers, basketball players, fiction writers, ice skaters, concert pianists, chess players, master criminals, and what have you, this number comes up again and again."2By 1593, the best plays in England were written by two poets who, we are told, followed very different paths, yet ended up producing work very similar in style and substance, each exhibiting an equal world-class mastery—Christopher Marlowe and William Shakespeare.

We can easily account for Marlowe’s achievement of mastery: He was granted a scholarship to the elite King’s School in Canterbury, and from there a Parker scholarship3to Cambridge (bestowed upon boys who could read music, sing, and compose verse), first for a Bachelor of Arts, and then continuing on scholarship for his Master of Arts. Marlowe perfected his ability to “make a verse” by translating Ovid’s Latin Amores into sophisticated English verse, the first vernacular translation of that work. Marlowe began to write plays while still at University, each work moving, by steep steps, toward mastery of his chosen field.

Shakespeare’s path had to have been very different. We do not know, but given his father’s position in the community it is reasonable to assume that Shakespeare attended the Stratford grammar school. It is thought he could not have stayed more than seven years, leaving at the age of fourteen. From then he must have worked, most likely in Stratford, since at age eighteen he married a local girl and began raising a family. By the age of twenty-one, he and his wife have three children, raising them in Stratford. Then the record goes blank. It resumes again when the first plays attributed to Shakespeare make their debut in London in the early 1590s. No one knows where Shakespeare was, or what he was doing, between starting a family in Stratford and debuting as a playwright in London, with plays which were immediately the equal of, if not better than, Marlowe plays written at nearly the same time.

How did Shakespeare achieve this feat? No one knows, but what is made clear in Gladwell’s book is that “genius” is an insufficient explanation. You also need roughly ten thousand hours of practice, a very difficult thing to achieve, as Gladwell explains:

It’s all but impossible to reach that number all by yourself by the time you’re a young adult. You have to have parents who encourage and support you. You can’t be poor, because if you have to hold down a part time job on the side to help make ends meet, there won’t be enough time left in the day to practice enough. In fact, most people can reach that number only if they get into some kind of special program—like a hockey all-star squad—or if they get some kind of extraordinary opportunity that gives them a chance to put in those hours.4This description applies perfectly to Christopher Marlowe. But could it also apply to Shakespeare?

If the research in Outliers is any indication, in order to produce plays and poetry which equalled Marlowe’s in refinement and skill, in the same time span, Shakespeare must have logged a similar amount of time studying and practicing as Marlowe (that they were the same age makes comparison easier). The burden rests on Shakespeare’s biographers to try and explain how this might have happened, or how it was even possible.

Those of us who argue that Christopher Marlowe wrote the works of Shakespeare have an explanation of where this fully-fledged Shakespearean mastery came from that is consistent with the research gathered in Outliers. We know that Marlowe (as is assumed of Shakespeare) was born a genius, but it was his environment, the lucky breaks he got in his childhood, his access to books, his scholarships, his leisure time to study and practice, his time to converse with other like-minded individuals, that made him, by 1593, arguably the greatest poet-playwright in England.

Shakespeare’s current biographers are wise enough to realize that “genius” is not a sufficient explanation, and they range far and wide to try and account for the incredible phenomenon of “Shakespeare”: He spent his youth as a page in the house of a nobleman; he was a teacher; he was a law-clerk; he patched up plays while on tour with acting troupes; he browsed book-sellers stalls and ended up equalling the learning of the university-educated. Since Shakespeare did achieve this mastery, the reasoning goes, one or more of these explanations must account for it. It is difficult to see how, though. Between working and raising a family Shakespeare had much going against him, perhaps as much as Marlowe had going for him. Gladwell’s summary also serves us here:

We pretend that success is exclusively a matter of individual merit. But there’s nothing in any of the histories we’ve looked at so far to suggest things are that simple. These are stories, instead, about people who were given a special opportunity to work really hard and seized it, and who happened to come of age at a time when that extraordinary effort was rewarded by the rest of society.5This explanation fits Marlowe’s story; could it also fit Shakespeare’s? What Shakespeare did or did not do during his formative years is unknown, and will probably remain unknown. But could he have had the opportunities, and the sheer number of hours necessary, to become a playwright who was able to write plays and poems at the same level of mastery as Marlowe’s in the same time-frame? This is not a question borne of snobbery, the usual retort tossed out when this issue is raised. Rather, it simply asks for an acknowledgment of the way the world actually works.

Daryl Pinksen

© Daryl Pinksen, August 2010

Daryl Pinksen, a founding member of the International Marlowe-Shakespeare Society, is the author of Marlowe's Ghost: The Blacklisting of the Man Who Was Shakespeare

1Gladwell, Malcolm. 2008. Outliers: The Story of Success. New York: Little, Brown and Company. p. 39.

[One of the many wonderful articles by Ericcson and his colleagues about the ten-thousand-hour rule is K. Anders Ericcson, Ralf Th. Krampe, and Clemens Tesch-Römer, “The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance,” Psychological Review 100, no. 3 (1993): 363-406.] Outliers Notes pp. 288-9.

2Gladwell. 2008. p.40.

[Daniel J. Levitan talks about the ten thousand hours it takes to get mastery in This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession (New York: Dutton, 2006), p. 197.”] Outliers Notes p. 289.

3Archbishop Matthew Parker’s scholarship was awarded to boys who could "at first sight to solf and sing plainsong" and to be "if it may be, such as can make a verse." http://www.marloweshakespeare.org/MarlowePartI.html

4Gladwell. 2008. p.42.

5Gladwell. 2008. p.67.

Click here for the blog's home page and recent content.