We caught up with Alex Jack, whose 2005 two-volume edition of Hamlet celebrates William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe as co-authors of the world's most famous play. Howard Zinn, author of the bestselling A People's History of the United States, hails Alex Jack's Hamlet as "remarkable" and "enormously impressive as a detective work in literature." Professor Jack has authored or edited more than 35 books on food and health, history, science, and the arts, including The Cancer-Prevention Diet (with Michio Kushi), The Mozart Effect (with Don Campbell), and Vegetarian Bride of Frankenstein. He is a macrobiotic teacher and counselor and divides his time between his home in the Berkshires in western Massachusetts and teaching in Europe. We're honored that he's taking the time with us.

Q: Professor, as we approach May 30, the anniversary of the alleged death of Christopher Marlowe, speak to us about what you think happened on that day in Deptford.

Alex: According to the history books, Marlowe died in a barroom brawl and after an official inquest was buried in an anonymous grave in the local churchyard. Case closed. In my view, the Elizabethan secret service, headed by the Cecils and Walsinghams, was unequalled in what today we would call clandestine ops. Its plots to frame and execute Mary Queen of Scots (several years before the May 30, 1593 affair) and Dr. Lopez, the Jewish physician to the Queen (a year later), testify to their ruthlessness and proficiency. Not only did they succeed in fooling their contemporaries, but also historians argue over their respective guilt to this day because of the murky intelligence trails left behind.

As recent scholarship shows, the “tavern” where Marlowe reputedly died was almost certainly a “safe house” used by the Cecils who were related to its proprietor, Madame Bull. Her establishment may also have been connected with Anthony Marlowe, the powerful head of the Muscovy Company, whose global trading operations were centered in Deptford, London’s port. Scholars are divided over whether Kit and Anthony were related. The Cecils were major investors in the Muscovy Company, and Anthony was connected with the London theater, so it’s likely there was some relationship, even if the two men shared only a common surname. But a possible connection between the two, while intriguing, is not essential to what transpired. In any event, the three men who were with Marlowe at the time of his death at the inn were all involved with the Cecils or Walsinghams in past or present intelligence activities. Though exonerated by the inquest, Ingram Frizer, Marlowe’s assailant, long continued to work for Marlowe’s friend and patron, Thomas Walsingham, after the deed.

Of course, ten days earlier, Marlowe had been arrested in connection with a heresy investigation. Though he was released on bail, he was clearly being set up as an example by Archbishop Whitgift and his cronies as part of a witch hunt against Separatists and freethinkers. The Cecils, notable enemies of Whitgift in the highest councils of state and Marlowe’s superiors in the secret service, evidently helped him disappear. They faked his death and put him, so to speak, in the Elizabethan witness protection program. As I speculate in my book, I don’t think they saved him for literary or artistic reasons per se, as they were not above sacrificing anyone for realpolitik. But Marlowe’s poetic genius, especially in the early history plays (later attributed to Shakespeare), were patriotic to the core and helped establish what today we would call the England brand. He was indispensable to the future of the Realm.

Just how the sting came down in Deptford is open to debate. It is not clear whether Marlowe was present, and it doesn’t really matter. My hunch is that he was, but “spirited” away when the corpse, probably of just executed Separatist clergyman John Penry, was substituted for his own (as alluded to later in Measure for Measure). Whether Queen Elizabeth was privy to the rescue before or after is also an open question. I tend to think she wasn’t, though other Marlovians feel she was. Archbishop Whitgift almost certainly was kept in the dark.

Marlowe’s escape route is also uncertain. Most probably he went across the Channel and through France and the Low Countries (possibly with the help of Poley, one of the three men he dined with on that fateful night, and who was a fellow spy and colleague) where he was an experienced intelligence operative. However, as I mention in my book, by coincidence or design, there was a vessel of the Muscovy Company that sailed from Deptford on June 1 for Scotland and thence the Baltics in which Kit could have fled north, completely erasing any probable southern trail in the event that the Archbishop and his allies on the Privy Council (who were essentially in charge of internal security in the country) got wind of the deception and launched their own dragnet to apprehend him, as they had for other religious fugitives.

In any event, what’s not in dispute is that about two weeks later the first book printed under Shakespeare’s name - the poem Venus and Adonis - comes out. The poem is in the style, meter, and characteristic mythological bent of Marlowe’s work Hero and Leander, that appeared earlier in the year. Kit’s literary fingerprints are all over the poem! The work was already in production and had been registered (and ironically approved by the Archbishop, who doubled as the chief censor) during the height of the Separatist controversy earlier in the spring. Subsequently, Two Gentlemen of Verona, Romeo and Juliet, The Merchant of Venice, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and the other sublime Italianate plays come out, at first anonymously and eventually some under Shakespeare’s name. So it’s pretty clear Marlowe went to Italy and the Continent for most of this period, up until about 1600, sending back manuscripts, probably via the Cecils’ network, through Walsingham’s own channels, or mutual friends and travelers.

Meanwhile, actor Will Shakespeare played his role as the loyal frontman and was handsomely rewarded with lavish payments and a coat of arms and kept the secret until his death. I profoundly disagree with anti-Stratfordians who put down Will as a country bumpkin akin to the “upstart crow,” the allusion in Greene’s Groatsworth of Wit that more than anything else confused scholars for the next four hundred years about Shakespeare’s timeline in London and early writing career. The reference to “Shake-scene” clearly points to Alleyn, the great actor, not Shakespeare, and is the entire crux or foundation for the modern Shakespeare literary-industrial complex, an unholy alliance of scholars (especially heads of English departments), theatre festivals, textbook publishers, and British politicians and hoteliers who have turned Stratford into a tourist Mecca.

In my view, Will Shakespeare deserves the Academy Award for best supporting actor of all time. On this basis, I cast him as co-author of Hamlet and the other plays and was roundly denounced by most of my fellow Marlovians! How could I sully the heavenly genius, “the darling of the Muses,” by giving equal billing to the dolt from Stratford? Will was certainly not a dolt for keeping quiet for thirty years when the Archbishop and Church of England would have probably given him the keys to Lambeth Palace and half its treasure for turning in Kit, or putting him to the rack if they suspected skullduggery at the Globe. (Of course, Will may not have known who the real identify of the playwright was, but regardless he kept mum about his own role!) So in my book, Will is every bit as noble as Marlowe, the lead actor in this drama, and both deserve to be sung to their heavenly literary and dramatic rest by angels from on high.

© The Marlowe-Shakespeare Connection, May 2009

Copies of the 400th anniversary edition of Hamlet by Marlowe and Shakespeare, with annotation and commentary by Alex Jack, are available for $35 postpaid from Amberwaves, PO Box 487, Becket MA 01223.

Alex’s web site is shakespeareandmarlowe.com, and he could be reached at shenwa@bcn.net.

Click here for our blog's home page and recent content.

Friday, May 29, 2009

Saturday, May 23, 2009

Who Was Eleanor Bull? by Samuel Blumenfeld

As we approach the anniversary of Marlowe's alleged death, it's sad that college students today have never heard of Christopher Marlowe. But the few who have will often ask, “Wasn’t he killed in a bar-room brawl?” The belief that Marlowe was killed in some seedy watering hole and then buried - case closed - is rampant, from the Eleventh Edition of the Britannica - “He was slain in a quarrel by a man variously named (Archer and Ingram) at Deptford at the end of May 1593, and he was buried at the lst of June in the churchyard of St. Nicholas at Deptford" - to a recent course description for "Marlowe and Shakespeare" at Williams College - "Marlowe was murdered, stabbed through the eye in a tavern brawl." Too often there's not even the mere recognition that so many of the details surrounding May 30, 1593, are highly disputable.

As we approach the anniversary of Marlowe's alleged death, it's sad that college students today have never heard of Christopher Marlowe. But the few who have will often ask, “Wasn’t he killed in a bar-room brawl?” The belief that Marlowe was killed in some seedy watering hole and then buried - case closed - is rampant, from the Eleventh Edition of the Britannica - “He was slain in a quarrel by a man variously named (Archer and Ingram) at Deptford at the end of May 1593, and he was buried at the lst of June in the churchyard of St. Nicholas at Deptford" - to a recent course description for "Marlowe and Shakespeare" at Williams College - "Marlowe was murdered, stabbed through the eye in a tavern brawl." Too often there's not even the mere recognition that so many of the details surrounding May 30, 1593, are highly disputable. It wasn’t until Harvard professor Leslie Hotson in 1925 managed to find the actual Coroner’s Inquest on Marlowe’s death in the Public Record Office that we were given the details of the “bar-room brawl.” In fact, Marlowe’s supposed demise did not take place in a bar-room, but in a very respectable guest house in Deptford run by an equally respectable widow by the name of Eleanor Bull. She was not just anybody. She was, in fact, distantly related to Lord Burghley (William Cecil), the Queen’s secretary of state and head of her intelligence service.

Park Honan, in his 2005 biography Christopher Marlowe: Poet and Spy, writes: “Mrs. Bull was a widow of good family lineage, whose likely discretion would have suited secret agents . . . Her ‘cousin’ Blanche Parry, Chief Gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber, had been a favourite of the queen.”

As for the bizarre events that took place that day, Honan writes: “The four guests who reached Mrs. Bull’s at about 10 a.m. were Marlowe, Ingram Frizer, Nicholas Skeres, and the ‘special messenger’ Robert Poley, who had just returned from the Hague. In need of privacy, they stayed all day at Mrs. Bull’s, which was not a tavern but a rooming-house in which meals were served. Her normal clientele would have included supervisors or inspectors at the dockyards, exporters of quality goods, and merchants involved in imports from Russia and the Baltic ports.”

As we know, Poley was one of Burghley's most experienced spies, and Frizer and Skeres were employees of Thomas Walsingham, Marlowe’s friend and patron. Mrs. Bull’s house was conveniently located only seven miles from Walsingham’s estate at Scadbury, where Marlowe had been staying after his arrest and release on bail.

Mrs. Bull’s husband Richard, who died in 1590, as a sub-bailiff assisted Christopher Browne, Lord of the Manor of Deptford and Clerk of the Green Cloth, in his manorial duties. And the Muscovy Company, a powerful trading company whose earliest investors were Elizabeth's inner circle of Lord Burghley and spymaster Sir Francis Walsingham, had a warehouse nearby Bull's house. Burghley and Walsingham, of course, played significant roles in Marlowe's "grooming" into the world of espionage.

Was Marlowe acquainted with Mrs. Bull’s house before the events of May 1593? Did Dame Bull's "connections" (through her late husband Richard, Lord Burghley, and Blanche Parry) play any role on May 30, 1593? And to a less likely but equally intriguing extent, did the Muscovy Company? And why Deptford? And why was Robert Poley, no secret service lightweight, there?

My theory is that Mrs. Bull’s role was to provide discrete hospitality for these secret agents and their plot. She saw no evil and heard no evil.

And many more questions remain.

Who is buried in the unmarked churchyard? Is it John Penry, whose body, I suspect, was the actual subject of the coroner’s inquiry? Penry, a Puritan activist, had been hanged the day before only two miles from Deptford. Was it Frizer and Skeres who retrieved the body and brought it back to Deptford? An order from the Secret Service would have facilitated that action. Strangely enough, no members of Penry’s family were permitted to attend the hanging or take possession of the body. In fact, no one knows whatever happened to Penry’s body or where it was buried.

Unfortunately, Honan, like so many other biographers of Marlowe, believes that the poet was killed at Deptford and that William Shakespeare was the great genius who wrote all the plays in the First Folio - published, coincidentally, by Edward Blount, Marlowe’s executor!

There is still a great deal to explore about the events in Deptford, and that is why my book and Daryl Pinksen's are so important. I have no doubt that in the near future irrefutable proof of Marlowe’s survival after Deptford will be found.

Samuel Blumenfeld

© Samuel Blumenfeld, May 2009

Samuel Blumenfeld, a World War II veteran of the Italian campaign, has authored more than ten books. His latest, The Marlowe-Shakespeare Connection: A New Study of the Authorship Question, was published by McFarland. He is a former editor in the New York book publishing industry and has lectured widely. His writings have appeared in such diverse publications as Esquire, Reason, Education Digest, Vital Speeches of the Day, Boston, and many others. He is a regular contributor to MSC.

See Sam on YouTube addressing the authorship controversy.

Click here for the blog's home page and recent content.

Monday, May 18, 2009

Marloviana: Measure for Measure & Kit Marlowe's Mother by Isabel Gortázar

Measure for Measure, Act III, scene 2, 190-1

Mistress Overdone:

My Lord, this is one Lucio’s information against me.

Mistress Kate Keepe-downe was with child by him in the Duke’s time;( … )

A name such as Mrs. Kate Keepe-downe is likely to draw the attention of those of us who believe that Kit Marlowe was the true author of the Shakespearian Canon. Kit’s mother, Katherine Arthur, married John Marlowe, a cobbler from Canterbury, becoming, therefore, Mrs. Katherine Marlowe. On the other hand, while Marlowe left to the murderous Catherine of Medici her full name in The Massacre at Paris, Shakespeare seems to have had a soft spot for the more familiar Kate. The shrewish but lovable Kate Minola is a good example. Then there is the French princess, Catherine de Valois, who marries Henry V; he calls her Kate from the start, even in the early version of the play, The Famous Victories of Henry the Fift. So, maybe, Katherine Marlowe was Kate for her family.

However, that was very flimsy evidence. I wondered whether there could be a hidden connection between Mistress Kate Keepe-downe and the real Mrs. Kate Mar-lowe? There is.

The Dukes of Vienna in Measure for Measure represent the Austrian Habsburg Emperors.1 This fact is clear from one of the two generally accepted sources for Measure: G. Cinthio's Story of Epitia, adapted by Shakespeare from one of the novellas in Cinthio’s collection of One Hundred Tales (Gli Hecatommithi), published in 1565.

In Cinthio’s story, the Emperor in question is referred to as Maximilian of Innsbruck, Innsbruck being for many years the capital of the Austrian Empire. Given the date of publication, Cinthio might have meant to refer to Maximilian II, who had succeeded to the Imperial Crown on the previous year. But whether Cinthio was referring to Maximilian I or Maximilian II, it seems that our wily author used his source, Epitia, to point at the Emperor Maximilian II, whose coronation took place in the year 1564.

Going back to the line: Mistress Kate Keepe-downe was with child (…) in the Duke’s time, we realize that the words in the Duke’s time are nonsense, because every time would have been one Duke’s time or another (Duke following Duke). So if we assume that Mrs. Overdone is referring to one specific Duke, then the sentence should be understood as something like: at the time of the (last) Duke’s death, or at the time of the (present) Duke’s coronation.

Now, two ladies possibly relevant to this line in Measure for Measure and its Mrs. Kate Keepe-downe were with child at the start of 1564: Mrs. Mary Shakespeare and Mrs. Kate Mar-lowe.

© Isabel Gortázar, April 2009

1The Habsburg family not only held the Holy Roman Empire for generations, but after Charles V (or Carolus), they held the Spanish Empire as well. Queen Elizabeth’s archenemy, Philip II of Spain, was Charles’s son and the head of the Habsburg family. After 1604 we will find Habsburgs in several Shakespearian plays; only in The Tempest there are six of them. But we also find Habsburgs in Marlowe’s Jew of Malta and Dr. Faustus.

Click here for the blog's home page and recent content.

Mistress Overdone:

My Lord, this is one Lucio’s information against me.

Mistress Kate Keepe-downe was with child by him in the Duke’s time;( … )

A name such as Mrs. Kate Keepe-downe is likely to draw the attention of those of us who believe that Kit Marlowe was the true author of the Shakespearian Canon. Kit’s mother, Katherine Arthur, married John Marlowe, a cobbler from Canterbury, becoming, therefore, Mrs. Katherine Marlowe. On the other hand, while Marlowe left to the murderous Catherine of Medici her full name in The Massacre at Paris, Shakespeare seems to have had a soft spot for the more familiar Kate. The shrewish but lovable Kate Minola is a good example. Then there is the French princess, Catherine de Valois, who marries Henry V; he calls her Kate from the start, even in the early version of the play, The Famous Victories of Henry the Fift. So, maybe, Katherine Marlowe was Kate for her family.

However, that was very flimsy evidence. I wondered whether there could be a hidden connection between Mistress Kate Keepe-downe and the real Mrs. Kate Mar-lowe? There is.

The Dukes of Vienna in Measure for Measure represent the Austrian Habsburg Emperors.1 This fact is clear from one of the two generally accepted sources for Measure: G. Cinthio's Story of Epitia, adapted by Shakespeare from one of the novellas in Cinthio’s collection of One Hundred Tales (Gli Hecatommithi), published in 1565.

In Cinthio’s story, the Emperor in question is referred to as Maximilian of Innsbruck, Innsbruck being for many years the capital of the Austrian Empire. Given the date of publication, Cinthio might have meant to refer to Maximilian II, who had succeeded to the Imperial Crown on the previous year. But whether Cinthio was referring to Maximilian I or Maximilian II, it seems that our wily author used his source, Epitia, to point at the Emperor Maximilian II, whose coronation took place in the year 1564.

Going back to the line: Mistress Kate Keepe-downe was with child (…) in the Duke’s time, we realize that the words in the Duke’s time are nonsense, because every time would have been one Duke’s time or another (Duke following Duke). So if we assume that Mrs. Overdone is referring to one specific Duke, then the sentence should be understood as something like: at the time of the (last) Duke’s death, or at the time of the (present) Duke’s coronation.

Now, two ladies possibly relevant to this line in Measure for Measure and its Mrs. Kate Keepe-downe were with child at the start of 1564: Mrs. Mary Shakespeare and Mrs. Kate Mar-lowe.

© Isabel Gortázar, April 2009

1The Habsburg family not only held the Holy Roman Empire for generations, but after Charles V (or Carolus), they held the Spanish Empire as well. Queen Elizabeth’s archenemy, Philip II of Spain, was Charles’s son and the head of the Habsburg family. After 1604 we will find Habsburgs in several Shakespearian plays; only in The Tempest there are six of them. But we also find Habsburgs in Marlowe’s Jew of Malta and Dr. Faustus.

Click here for the blog's home page and recent content.

Marloviana: The Tempest's "Every third thought" by Isabel Gortázar

The Tempest Act V, 1, 311-312

Prospero:

And thence retire me to my Milan, where,

Every third thought shall be my grave.

The "Every third thought" line has puzzled the Stratters, and with reason. Of course, once you focus on Marlowe, it becomes easy to “translate." The Tempest is full of numerical clues and this is one of them. Here is what I wrote about it in my essay on The Tempest (Marlowe Research Journal nº 4):

Click here for the blog's home page and recent content.

Prospero:

And thence retire me to my Milan, where,

Every third thought shall be my grave.

The "Every third thought" line has puzzled the Stratters, and with reason. Of course, once you focus on Marlowe, it becomes easy to “translate." The Tempest is full of numerical clues and this is one of them. Here is what I wrote about it in my essay on The Tempest (Marlowe Research Journal nº 4):

Even accepting the obvious meaning that Prospero is getting old and is thinking about death, this is a curious way of putting it. Why every third thought? Is this a manner of speaking, or is it one more example of his excessive use of the number three? Is the author positively linking his grave to the number three? When I focused on this strange line, it occurred to me that Marlowe would be the only one, among the authorship candidates, who could actually know the date of his burial: 1st June 1593. And here it seems I may have struck gold:

As Marlowe had been killed on May 30th, the 1st of June was the third day from his death (in the same way that Christ is supposed to have resurrected on the third day, Easter Sunday, from his death on Good Friday). Also, June is the third month in the Julian Calendar Year, which starts on March 25th. Finally, 1593, as well as 1+5+9+3=18, and 1+8 =9 (= 3+3+3) are numbers divisible by three. So, Marlowe’s grave, though unmarked, would have received his corpse on the third day after his death, on the third month of the Julian Year 1593, a year divisible by three whichever way one adds its digits. I wonder what are the odds that all this may be a coincidence.

Click here for the blog's home page and recent content.

Sunday, May 10, 2009

Was Shakespeare Catholic?: Making Sense of Will's Self-Concealment by Daryl Pinksen

Scholars have long expressed frustration that Shakespeare left behind so few personal traces. There is plenty of evidence of a business life, but nothing concerning literary matters. Compounding their frustration, Shakespeare’s plays seem to suggest a desire to remain deliberately impersonal, to keep himself and his real opinions concealed.

Scholars have long expressed frustration that Shakespeare left behind so few personal traces. There is plenty of evidence of a business life, but nothing concerning literary matters. Compounding their frustration, Shakespeare’s plays seem to suggest a desire to remain deliberately impersonal, to keep himself and his real opinions concealed.Why did this particular author, the one we most want to know, choose to hide his face? The quest for an answer reminds us that “Shakespeare,” as an historical literary phenomenon, requires an explanation.

The exploration of Shakespeare’s Catholic roots has provided Michael Wood, the filmmaker behind the four-part documentary In Search of Shakespeare, with an opportunity to suggest an answer – that Shakespeare lived his life as a hidden Catholic, and the fear of drawing the attention of Protestant authorities to his forbidden beliefs necessitated a low literary profile.

The case for Shakespeare’s father John’s Catholicism is solid. Evidence from his life and more from his will leaves little doubt that he kept his loyalty to the old faith in spite of the state’s attempts to stamp it out. Shakespeare’s youth then was spent in a home that paid lip-service to the upstart Anglican religion. The textual evidence for the author’s Catholicism is less sure, but more passionately argued. Scholars have constructed opposing views with equally strong ammunition from the same texts. This is part of the frustration. The collected Shakespeare plays, though finite in number, create a near infinite space within which we interact with his creation.

The author’s intimate knowledge of religious matters, including the history and practice of the Catholic Church, hints to Wood and others that the author was a devout Catholic. But we must take into consideration that the author was a Renaissance polymath of the highest degree. Those who forget this fact waste time speculating, for example, that demonstrated expertise in legal matters means the author worked in a law office – or that he was Francis Bacon. Likewise, an easy familiarity with courtly matters, and a broad acquaintance with continental Europe and its politics, tells others the author was the Earl of Oxford. A handful of knowing references to leathercraft leads scholars like Jonathan Bate to imagine the poet’s youth spent as the son of a glover.1

After outlining Shakespeare’s family’s Catholic roots and some contemporary accounts of Catholics persecuted by the state, Wood, in his companion book Shakespeare (2003), reveals why Shakespeare’s supposed Catholic faith is so important:

Such hints might tend to suggest that the absence of personal revelation in his works, which has so exercised his modern readers, and fuelled the fantasies of the conspiracy theorists, is no accident but a deliberate act of self-concealment on his part. This would make complete sense in someone of his background, whose family religion was defined by the law as treason, and whose father was pursued by the government’s bounty hunters and thought police.2[my italics]But could the author’s private Catholic beliefs have really produced a life-long fear resulting in deliberate literary self-concealment? As often when discussing Shakespeare in his world, we can look for a comparison to Shakespeare’s contemporary Ben Jonson. A player for the Admiral’s Men, Jonson made his playwrighting debut as a contributor to the 1597 Isle of Dogs, a seditious play which landed him in jail. A year later, Jonson was back in jail for killing a fellow player, Gabriel Spencer, in an illegal duel. Jonson escaped hanging for his crime because of a legal loophole, the ancient “right of clergy,” which allowed those fluent in Latin to get a second chance. Instead, Jonson forfeited all his possessions.

Here is where the Jonson comparison becomes relevant. While in prison, Jonson actually converted to Catholicism and remained openly Catholic for twelve years.3 And even though he stopped practicing his faith in 1610, it is widely believed that he returned to Catholicism later in life.4

This is curious. Shakespeare, we are asked to believe, was so fearful of his “hidden” Catholic beliefs being outted that it led to a life-long “deliberate act of self-concealment.” Jonson, by contrast, while trying to build a reputation, chose to become an open Catholic. What impact did Jonson’s conversion have on his career? It did not slow him down for an instant. Upon release from prison in 1598 he effected a comeback with Every Man Out of His Humour, a hit for Shakespeare’s Lord Chamberlain’s Men. His career continued on an upward trajectory culminating in 1616 when King James I named Jonson the first de-facto poet laureate by granting him an annual pension of 100 marks.5

Scholars are quick to point to Ben Jonson when needing an example of another playwright who began as a player, or one who had not gone to the university. They should also remember Jonson when considering the theory that Shakespeare’s remarkable literary self-concealment was the outcome of hidden Catholic beliefs. Ben Jonson, minor actor, ex-con son of a bricklayer, was not impeded in his writing career by his open Catholic beliefs. Can we really be expected to believe that the author of the Shakespeare plays was paralyzed with fear into a literary life lived under cover because of hidden Catholic beliefs?

In light of Jonson’s experience, it appears that Wood may be exaggerating the danger of Catholicism in 1590s England. Simply being Catholic was not an act of treason. It was only when those Catholics declared their Protestant monarch illegitimate that treason was charged against them.

Perhaps Shakespeare was just more cautious than Jonson? We know Shakespeare was not the shy and retiring type; witness his pursuit of a coat of arms, padded with spurious embellishments, and his huge Stratford home. And living in London as an actor/shareholder with a theater company that performed at court could not be considered “low-profile.”

If Shakespeare did hold private Catholic beliefs, he would not have needed to live his literary life in fear. He did not need to avoid recording personal remembrances – letters, dedications, encomia, prefaces; all he needed to do was avoid making anti-establishment statements in them.

Still, the fact remains that the author of the Shakespeare plays, whoever he was, did employ a policy of literary self-concealment. The answer to why he chose to do so lies elsewhere.

Daryl Pinksen

© Daryl Pinksen, May 2009

Daryl Pinksen, a regular MSC contributor, is the author of Marlowe's Ghost, Grand Prize Winner of the 17th Annual Writer's Digest International Self-Published Book Awards.

1Bate, Jonathan. 2002. "Scenes from the Birth of a Myth and the Death of a Dramatist." In Shakespeare’s Face. Stephanie Nolen. Canada: Alfred A. Knopf. p.122.

2Wood, Michael. 2003. Shakespeare. New York: Perseus Books Group. p.27.

3Harp, Richard, and Stewart, Stanley, eds. 2000. The Cambridge Companion to Ben Jonson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. xiv.

4Van Den Berg, Sara. 2000. "True Relation: the Life and Career of Ben Jonson." In The Cambridge Companion to Ben Jonson. Richard Harp and Stanley Stewart eds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p.10.

5Marcus, Leah. 2000. "Jonson and the Court." In The Cambridge Companion to Ben Jonson. Richard Harp and Stanley Stewart eds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p.36.

Click here for the blog's home page and recent content.

Sunday, May 3, 2009

The Grafton Portrait and Kit Marlowe's Dangerous Living by Isabel Gortázar

In the Marlowe Society Newsletter Nº 30, (Spring 2008), there are two articles, by Donna Murphy1 and Stewart Young2 respectively, shedding new light on Marlowe’s youthful habits and proving, almost beyond reasonable doubt, that he was fond of drink, tobacco and women.

In the Marlowe Society Newsletter Nº 30, (Spring 2008), there are two articles, by Donna Murphy1 and Stewart Young2 respectively, shedding new light on Marlowe’s youthful habits and proving, almost beyond reasonable doubt, that he was fond of drink, tobacco and women. What follows is part of my reply3 to both Murphy’s and Young’s articles. Since the alleged portraits of Shakespeare are so much in the news of late, and since the speculative pirouettes of Prof. Stanley Wells in regard to the Janssen/Cobbe Portrait encourage us to propose almost any theory in respect of the other portraits, I thought I’d put forward a hypothesis about the Grafton Portrait. I must say I am grateful to Dr. Wells for being so sure that the Janssen/Cobbe is the genuine article, as that leaves the Chandos, which I believe to be Marlowe’s, a non-starter for Shakespeare.

In order to elaborate my hypothesis about the Grafton, I need to comment on that extreme thinness of Marlowe’s, about which we have heard several echoes, including the lines in The Scholler, quoted by Murphy in her article: That mickle study make men lean, / As well as doth a curst queane…

There are several clues in Shakespeare to extraordinary thinness.4 We have Falstaff’s declaration that he used to be as thin as an eagle’s talon,5 which matches the information, in The Boy’s Song, that at the time of his stay with Sir John Harington6 under the alias of Mr. Le Doux, Marlowe, the author of Song, was lark’s-heels trim; lark’s heels and eagle’s talons sound to me too similar, as metaphors go, for coincidence. Then we should take into account the meaning of the Latin-derived name Macilente (pale and thin). Macilente is a character in Ben Jonson’s play Every Man Out of His Humour; I believe that this character represents Marlowe. In the play’s last speech, Macilente (in theory addressing himself to the Queen), wishes that you may in time make lean Macilente as fat as Sir John Falstaff; so, lean Macilente, stressing the original meaning of the name.

On the basis of all these clues, I had come to the conclusion that Marlowe had been unwell, and probably very thin, from, say, 1595 till 1599, the year of Every Man Out. I also conjectured that it could have been such illness the reason why Essex, or Anthony Bacon on his behalf, had asked Sir John Harington the favour of giving shelter and a teaching job to Marlowe-Le Doux, as some of us believe he did during at least part of 1595-6.7 These years’ span would fit with the publication dates of the 1Q Henry IV Part One (1598), with the wedding (June 1595) of Elizabeth De Vere -first-born child of Ver- to the Earl of Derby, mentioned in The Boy’s Song,8 as well as with the dates of publication of Sir John Davies’s Epigrams about Faustus and his loss of hair due to his having seene a Lyoness.9

Now it appears that Marlowe’s infection and consequent loss of weight (and hair?) may have happened, according to Murphy’s references, as early as 1588, when Robert Greene’s Perimedes was published, and no later than 1590, the year of publication of The Cobler of Canterburie with its lean Scholler. This does not preclude the possibility that Marlowe may have suffered the emaciating effects of such infection for several years after the disease itself had disappeared, and it would not be fanciful to imagine that the events in May 1593 might have made matters worse. As Falstaff says: a plague of sighing and grief! it blows a man up like a bladder!10 - which of course may be taken to mean exactly the opposite, vg: that a plague of sighing and grief can reduce a man to a skeleton. This interpretation would confirm Macilente’s last comment, in the sense that it would be in the Queen’s power to dispel Marlowe’s plague of sighing and grief, so he could become as fat as Sir John Falstaff. I also suspect that Marlowe created a fat, witty, clown in parody of his emaciated self.

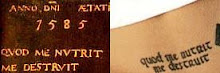

The conjecture that Marlowe may have caught a venereal disease in, or before, 1588, losing a lot of weight as a result, presents us with the intriguing possibility that he may be the sitter in the Grafton Portrait. Let us remember some facts: In 1587 Marlowe had obtained his Cambridge degree, he had been involved in important spy work for the Crown, he had obviously decided against ordination and had plunged instead into a dramatist’s life, writing his first serious play: Tamburlaine the Great. And so, by 1588, having found his own mighty voice, Marlowe had become famous. He was now a popular man with powerful patrons (and the success probably went to his head). Friends and foes spoke of him, or wrote about him, his eccentricities were noted, apparently his illnesses too. Would it be too extravagant to surmise that the same person – patron, relative or whatever - who had paid in 1585 for the portrait in Corpus Christi College, paid for a new portrait of the up-and-coming new genius?

The so-called Grafton Portrait of Shakespeare bears the date 1588; the age of the sitter is 24 years. We are presented with a thin young man with short, dark hair and beard, dressed in clothes remarkably like the clothes that Marlowe (if it is Marlowe) is wearing in the Corpus Christi Portrait; the mouth, nose and eyes are very similar despite the thinness, the moustache is identical, and the higher forehead and receding hair-line may suggest premature loss of hair.

But what do we know about the Grafton Portrait? To begin with, we have been told that it cannot possibly be a portrait of William Shakespeare. (The National Portrait Gallery issued that statement in October 2005, a statement further supported by Dr. Wells’s recent declarations about the Janssen/Cobbe Portrait), which leaves us with the task of finding another man born in 1564 who might qualify.

One curious detail observed by the specialists was that the number 24, in AE SVAE, 24, was altered from an original 23, and it has been suggested that the sitter passed his 24th birthday before the portrait was finished, and he requested that his age be changed accordingly. If the portrait took longer to paint than expected, the year and the sitter’s age might have changed. (And this might be the place to remember that, as I pointed out in a previous article,11 if the Aetatis of a subject was fixed according to the year of their date of birth and not as regnal years, the age of William Shakespeare on 23rd April 1616 was 52 years, not 53, as carved in the Stratford Monument. And thereby hangs a tale.)

If the young man were Marlowe, the portrait may have been started late in 1587, to celebrate perhaps his Cambridge degree; then it was suddenly interrupted. The painter had time enough to include the AE SVAE, 23, but not the year. Then the portrait could have been resumed at any time after March 25th (or much later in the year), in any case after Marlowe’s 24th birthday; so the AE SVAE had to be altered.

According to further information released by the National Portrait Gallery, we also know that, although a specific artist has not been identified, the portrait was painted in England, in the late sixteenth century, on wood deriving from a tree grown in the areas around Surrey and London, both of which areas border with Kent, Marlowe’s county of birth. This is apparently a rarity, as professional painters of the period generally used wood from the Baltic region.

But how could a portrait of Marlowe be linked to Grafton Regis? Not until the early 20th century did the Grafton Portrait obtain that name, when its owners - the Ludgate family from Grafton Regis - claimed an old family tradition by which the portrait had been bequeathed by one of the Dukes of Grafton to their ancestor, a yeoman farmer, five or six generations previously.

And here is a long shot: If the portrait had been the possession of the early Dukes of Grafton, it might conceivably have come to them from the Palmer family. The first Duke, Henry Fitz-Roy, was the illegitimate son of the notorious Duchess of Cleveland, mistress of Charles II and wife of the unfortunate Roger Palmer, whose Catholic faith did not allow him to seek a divorce, despite the Duchess’s scandalous behaviour. As Palmer had no children outside his marriage (and there are serious doubts as to his having fathered any of his wife’s), it would not be adventurous to guess that some heirlooms he may have inherited from his own family passed on to her children, one of whom was created first Duke of Grafton in 1675 by his royal father. So, if by any chance the portrait was originally owned by the Palmer family this would explain why one of the early Dukes would think so little of it as to bequeath it to a stranger, particularly if there were something “embarrassing” about the identity of the sitter.

And what seems relevant at this point is that Roger Palmer’s direct ancestor, Sir Thomas Palmer, 1st Baronet of Wingham (1540-1624/5), was Sheriff of Kent during the lifetime of Christopher Marlowe. Therefore, all things considered and after five hundred years of posing as Shakespeare merely on the grounds of that AE SUAE.24, it seems not impossible that the lean young man may have been Marlowe after all.

Isabel Gortázar

© Isabel Gortázar, April 2009

Isabel Gortázar can be reached at igortazar@violaservices.com

1Donna N. Murphy: "Clues About Christopher Marlowe’s Sexuality in John Davies’ Epigrams and The Cobler of Canterburie." The Marlowe Society Newsletter, nº 30, Spring 2008.

2Dr. Stewart Young: "That All They That Loue Not Tobacco & Boies Were Fooles, an Opinion Attributed to Christopher Marlowe by Richard Baines, May 1593." The Marlowe Society Newsletter, nº 30, Spring 2008.

3"Tobacco, Booze and Women: Kit Marlowe’s Dangerous Living." The Marlowe Society Newsletter, nº 32, Spring 2009.

4Needless to say, I believe that Christopher Marlowe is the author of the Shakespeare works, including The Boy’s Song in The Two Noble Kinsmen.

51 Henry IV (II, 4, 323) Falstaff: …when I was about thy years, Hal, I was not an eagle's talon in the waist; I could have crept into any alderman's thumb-ring: a plague of sighing and grief! it blows a man up like a bladder. (1Q HIV, publ. 1598, and FF.).

6The Boy’s Song: Second Stanza:

Primrose, first-born child of Ver/Merry springtime’s harbinger/With harebells dim, Oxlips,in their cradles growing/Marigolds on deathbeds blowing/Lark’s-heels trim.

My own interpretation of The Boy’s Song would by far exceed the limits of this article, but I agree with some of Sandra Lauder’s interpretations, specifically her suggestion that harebells mean ha-ring-ton. (Sandra Lauder: "An Examination of ‘The Boy’s Song'": The Marlowe Society Research Journal nº 4, September 2006).

7A series of letters, passports and other documents, as well as a list of books including some of Shakespeare’s known sources (The Bacon Papers. Lambeth Palace Archives), led A.D. Wright to propose that a Mr. Le Doux, the supposed owner of these papers and books, may have been Marlowe. This Mr. Le Doux had apparently been hired by Sir John Harington of Exton as tutor to his young son. I agree with Wright’s theory, not least because of the added scene (IV, 1) in The Merry Wives of Windsor (FF), which does not appear in the 1Q. Although Wright does not mention the scene in The Merry Wives, the Le Doux theory was explained in depth in her book: Shakespeare. New Evidence. 1996.

8I believe that The Boy’s Song that was later included in The Two Noble Kinsmen (by Shakespeare and Fletcher), was originally written by Marlowe, for a private family party during the Christmas/New Year festivities in 1604-5, to celebrate the marriage of Susan de Vere to Philip Herbert, Earl of Montgomery. In the Song, the author reminisces on the previous marriage, in 1595, of the bride’s elder sister, Elizabeth de Vere, to the Earl of Derby. Shakespeare is supposed to have written Midsummer’s Night’s Dream for that occasion. MND includes the marriage between Theseus and Hippolyta, queen of the Amazones. The Two Noble Kinsmen opens precisely with the marriage feast of Hippolyta and Theseus, which can hardly be a coincidence. The exact date of composition of TNK is unknown, but cannot be earlier than 1606, when John Fletcher started his career as a dramatist.

9Published, according to Murphy, in 1595/6.

10See Footnote 5.

11"Let’s Talk of Graves and Worms and Epitaphs." The Marlowe Society Newsletter 27, Autumn 2006.

Click here for the blog's home page and recent content.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)