Tuesday, December 1, 2015

The Marlowe Papers on Stage

Purchase tickets today for The Marlowe Papers: A One-Man Play at Otherplace at the Basement (24 Kensington St, Brighton). This is an exciting new stage version of Ros Barber's critically acclaimed verse novel The Marlowe Papers which will run from January 26-January 30.

Wednesday, October 21, 2015

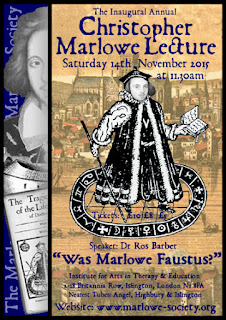

Was Marlowe Faustus? Ros Barber @ London Art House, November 14

Dr. Ros Barber, contributor to this blog and winner of the Desmond Elliott Prize for her highly acclaimed verse novel The Marlowe Papers, will be presenting at the Marlowe Society's inaugural Annual Christopher Marlowe Lecture on the topic "Was Marlowe Faustus?" Here is a summary of Dr. Barber's lecture:

"We do not know exactly when Doctor Faustus was written, but Robert Greene's 1588 allusion to Marlowe associates him, very early in his career, with a famous magician. Faustus is the protagonist with whom Marlowe is most often conflated: the scholar A.L.Rowse said 'Marlowe is Faustus'. Is this simply a case of reading the author's life backwards through the lens of his public atheism and subsequent sticky end? Were elements of Marlowe's biography written in to the play after his death? Did those who knew him personally think of him as Faustus? This talk explores evidence that illuminates Marlowe's relationship with his most famous protagonist."

Click here to purchase tickets. The London Art House is located at 2-18 Britannia Row, Islington, London.

"We do not know exactly when Doctor Faustus was written, but Robert Greene's 1588 allusion to Marlowe associates him, very early in his career, with a famous magician. Faustus is the protagonist with whom Marlowe is most often conflated: the scholar A.L.Rowse said 'Marlowe is Faustus'. Is this simply a case of reading the author's life backwards through the lens of his public atheism and subsequent sticky end? Were elements of Marlowe's biography written in to the play after his death? Did those who knew him personally think of him as Faustus? This talk explores evidence that illuminates Marlowe's relationship with his most famous protagonist."

Click here to purchase tickets. The London Art House is located at 2-18 Britannia Row, Islington, London.

Tuesday, October 20, 2015

Ros Barber at Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship Conference

Click here to listen to the International Marlowe-Shakespeare Society's Ros Barber discuss the underlying reasons for the Shakespeare authorship question. Dr. Barber recently attended the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship conference in Ashland,

Oregon, to give a paper on "The Value of Uncertainty." The recording is from Jefferson Public Radio, Ashland, Oregon, 23 Sep 2015.

Monday, June 1, 2015

Sam Blumenfeld, 1926-2015

It is with great sorrow that I report the passing of Sam Blumenfeld. In 2008, Sam called me up to float the idea of my starting a blog on the Marlowe-as-Shakespeare theory. It was Sam's phone call that inspired me to give it a shot.

My first communication with Sam was in 1993. I was 25 years old and teaching high school English in the South Bronx, and I was horrified by how many incoming 9th graders struggled with reading. It was Sam's Alpha-Phonics reading system that assisted me in teaching kids the right way to read - kids who had sadly graduated from New York City public middle schools as shockingly poor readers. Alpha-Phonics, I had discovered, was the quickest way to repair the damage of dubious reading strategies, such as look-say and whole language, or flat-out ineffective reading instruction in general. Alpha-Phonics was a godsend, and I employed "guerilla" teaching by sneaking his intensive, systematic system into my daily class lessons so that I could ensure that at least my students became proficient in letter-sound relationships. Along with Rudolf Flesch, I consider Sam to have been the most effective, articulate, and influential critic of bad reading methods in American schools, methods he was not afraid to label "educational malpractice."

Sam was a legendary pioneer in America's flourishing homeschool movement, in part because Alpha-Phonics empowered thousands upon thousand of parents to teach their kids how to read correctly, and he was a tireless proponent of common sense pedagogical strategies, such as intensive, systematic phonics. I attended homeschool conferences with Sam, and I saw firsthand how parents couldn't wait to thank him for his how-to instructional materials and relentless defense of homeschooling in countless publications and forums. Browse the Amazon reader reviews of his Alpha-Phonics reading system and you'll get a sense of the positive impact he had on so many lives.

To calculate how many speeches Sam has given in his lifetime at conventions and conferences is impossible, but they are in the many hundreds. I know that he had lectured in all 50 states.

Sam was born in New York City, was a World War II veteran of the Italian campaign, was fluent in French, and was widely published on a diverse range of topics (one of his first "big" pieces was "How to Marry a Rockefeller," Esquire, 1974). He truly led an exciting life, and here's one of my favorite anecdotes of his: "I did meet Ayn Rand when I was editor at Grosset & Dunlap. Took her to lunch. I then attended the Objectivist lectures given by her protege Nathaniel Branden. Rand would come at the end of each lecture and answer questions. After the lecture, a group of us would retire to the bar in the hotel for further dicussion. Alan Greenspan was part of that group. Of course, Rand later broke off with Branden because he was in love with a younger woman."

Sam was a passionate Marlovian, and in the 1960s he was a close acquaintance of Calvin Hoffman, who pioneered the "Marlowe as hidden hand behind Shakespeare" theory in the mid 1950s. Two years ago, Sam turned over to me all of his correspondences between Hoffman and him - what a treasure trove for Marlovians!

In 2009, I had a former student of mine interview Sam regarding the Marlowe-as-Shakespeare theory. Click here for the interview.

Also in 2009, Sam - along with Peter Farey, Dr. Ros Barber, Daryl Pinksen, Mike Rubbo, Isabel Gortázar, and myself - co-founded the International Marlowe-Shakespeare Society.

Sam was a kind and generous man who valued authentic conversation and lively debate, and he was so well-versed on so many issues. Until the very end, he was a fiercely passionate advocate of causes near and dear to his heart, especially the absolutely vital mission of teaching children - and even adults - how to read.

Rest in peace, Sam.

My first communication with Sam was in 1993. I was 25 years old and teaching high school English in the South Bronx, and I was horrified by how many incoming 9th graders struggled with reading. It was Sam's Alpha-Phonics reading system that assisted me in teaching kids the right way to read - kids who had sadly graduated from New York City public middle schools as shockingly poor readers. Alpha-Phonics, I had discovered, was the quickest way to repair the damage of dubious reading strategies, such as look-say and whole language, or flat-out ineffective reading instruction in general. Alpha-Phonics was a godsend, and I employed "guerilla" teaching by sneaking his intensive, systematic system into my daily class lessons so that I could ensure that at least my students became proficient in letter-sound relationships. Along with Rudolf Flesch, I consider Sam to have been the most effective, articulate, and influential critic of bad reading methods in American schools, methods he was not afraid to label "educational malpractice."

Sam was a legendary pioneer in America's flourishing homeschool movement, in part because Alpha-Phonics empowered thousands upon thousand of parents to teach their kids how to read correctly, and he was a tireless proponent of common sense pedagogical strategies, such as intensive, systematic phonics. I attended homeschool conferences with Sam, and I saw firsthand how parents couldn't wait to thank him for his how-to instructional materials and relentless defense of homeschooling in countless publications and forums. Browse the Amazon reader reviews of his Alpha-Phonics reading system and you'll get a sense of the positive impact he had on so many lives.

To calculate how many speeches Sam has given in his lifetime at conventions and conferences is impossible, but they are in the many hundreds. I know that he had lectured in all 50 states.

Sam was born in New York City, was a World War II veteran of the Italian campaign, was fluent in French, and was widely published on a diverse range of topics (one of his first "big" pieces was "How to Marry a Rockefeller," Esquire, 1974). He truly led an exciting life, and here's one of my favorite anecdotes of his: "I did meet Ayn Rand when I was editor at Grosset & Dunlap. Took her to lunch. I then attended the Objectivist lectures given by her protege Nathaniel Branden. Rand would come at the end of each lecture and answer questions. After the lecture, a group of us would retire to the bar in the hotel for further dicussion. Alan Greenspan was part of that group. Of course, Rand later broke off with Branden because he was in love with a younger woman."

Sam was a passionate Marlovian, and in the 1960s he was a close acquaintance of Calvin Hoffman, who pioneered the "Marlowe as hidden hand behind Shakespeare" theory in the mid 1950s. Two years ago, Sam turned over to me all of his correspondences between Hoffman and him - what a treasure trove for Marlovians!

In 2009, I had a former student of mine interview Sam regarding the Marlowe-as-Shakespeare theory. Click here for the interview.

Also in 2009, Sam - along with Peter Farey, Dr. Ros Barber, Daryl Pinksen, Mike Rubbo, Isabel Gortázar, and myself - co-founded the International Marlowe-Shakespeare Society.

Sam was a kind and generous man who valued authentic conversation and lively debate, and he was so well-versed on so many issues. Until the very end, he was a fiercely passionate advocate of causes near and dear to his heart, especially the absolutely vital mission of teaching children - and even adults - how to read.

Rest in peace, Sam.

Tuesday, May 26, 2015

Ros Barber on the "New" Shakespeare Portrait

Click here for Ros Barber's fantastic piece, "Why the 'New Shakespeare Portrait' Is Not Shakespeare," in the Huffington Post. Ros Barber, a regular contributor to this blog and a co-founder of the International Marlowe-Shakespeare Society, is the author of The Marlowe Papers.

Monday, April 20, 2015

The Similarity Between the Marlowe and Shakespeare Coats of Arms by Dave Randall, with Donna N. Murphy

A short time ago I was looking up something in Burke’s The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales when I decided to check the entries for Marlowe.1 There are several coats-of-arms for various branches of the Marlowe family listed; most are what are called "canting arms" and display a heraldic device called a martlet, which is basically a sparrow without feet, and are a pun between "martlet" and "Marlowe." The one that caught my eye, however, was this entry: "Marlow, or Marley, Or, a bend sable":

These arms are identical to those granted to John Shakespeare in 1596, minus the spear which appears on the Shakespeare arms:

Since there is no date associated with the Marlow/Marley arms, it is probable that they were in use prior to what is called the "first visitation" in 1483, when all of the arms in England were first recorded and a comprehensive list compiled by the heralds.

Since we know little about John Marlowe's ancestry, we cannot say whether he was from a family entitled to bear arms, but it is not beyond the realm of possibility; many relatively humble people (like Shakespeare's mother) were from armigerous families. We also do not know if Marlowe was related to the branch of the family that used these arms. Yet this may not have mattered, if the point was to associate the names “Shakespeare” and “Marlowe” via heraldry.

Might this be another authorship clue? Might some friend of Marlowe have influenced or bribed William Dethick, the Garter King of Arms who granted John Shakespeare his arms, to assign the Shakespeares a coat-of-arms almost identical to the Marlowes? Might he have done so to signal “those in the know” regarding the true authorship of the “Shakespeare” works?

In 1602, York Herald of Arms Ralph Brooke accused Dethick of improperly granting a coat-of-arms to 23 “mean persons,” including Shakespeare. He also alleged that Shakespeare’s design was too close to that of Lord Mauley:

With the aid of William Camden, playwright Ben Jonson’s former mentor, Dethick successfully defended his decisions regarding Shakespeare and the design of the coat of arms.2 It was Jonson who satirized Shakespeare’s coat-of-arms via the character Sogliardo in Every Man Out of his Humour (wr. 1599), and then later sang Shakespeare’s praises in the Bard’s First Folio, 1623. Diana Price has proposed that Jonson knowingly differentiated between the actor from Stratford-upon-Avon and the main author of the Shakespeare canon.3

In sum, if all of this is merely a coincidence, it is a very strange one.

© Dave Randall and Donna N. Murphy, April 2015

These arms are identical to those granted to John Shakespeare in 1596, minus the spear which appears on the Shakespeare arms:

Since there is no date associated with the Marlow/Marley arms, it is probable that they were in use prior to what is called the "first visitation" in 1483, when all of the arms in England were first recorded and a comprehensive list compiled by the heralds.

Since we know little about John Marlowe's ancestry, we cannot say whether he was from a family entitled to bear arms, but it is not beyond the realm of possibility; many relatively humble people (like Shakespeare's mother) were from armigerous families. We also do not know if Marlowe was related to the branch of the family that used these arms. Yet this may not have mattered, if the point was to associate the names “Shakespeare” and “Marlowe” via heraldry.

Might this be another authorship clue? Might some friend of Marlowe have influenced or bribed William Dethick, the Garter King of Arms who granted John Shakespeare his arms, to assign the Shakespeares a coat-of-arms almost identical to the Marlowes? Might he have done so to signal “those in the know” regarding the true authorship of the “Shakespeare” works?

In 1602, York Herald of Arms Ralph Brooke accused Dethick of improperly granting a coat-of-arms to 23 “mean persons,” including Shakespeare. He also alleged that Shakespeare’s design was too close to that of Lord Mauley:

With the aid of William Camden, playwright Ben Jonson’s former mentor, Dethick successfully defended his decisions regarding Shakespeare and the design of the coat of arms.2 It was Jonson who satirized Shakespeare’s coat-of-arms via the character Sogliardo in Every Man Out of his Humour (wr. 1599), and then later sang Shakespeare’s praises in the Bard’s First Folio, 1623. Diana Price has proposed that Jonson knowingly differentiated between the actor from Stratford-upon-Avon and the main author of the Shakespeare canon.3

In sum, if all of this is merely a coincidence, it is a very strange one.

© Dave Randall and Donna N. Murphy, April 2015

1Burke, Bernard. The General Armory of England, Scotland, and Wales (London: Harrison and Sons, 1864), Vol. II.

2Donaldson, Ian. Ben Jonson: A Life (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 160-161.

3Price, Diana. Shakespeare's Unauthorized Biography (Shakespeare-authorship.com, 2012), 66-75, 202-15.

Saturday, March 14, 2015

Looking for William Hall by Donna N. Murphy

In The Shakespeare

Conspiracy, Graham Phillips and Martin Keatman set down four intriguing

occurrences in archival records (dated between 1592 and 1603) of the name

William or Will Hall, plus one of Hall, that appeared to connect him to the

world of British intelligence.1 The authors conjectured that William Shakespeare from

Stratford-upon-Avon was a secret agent who employed the name as an alias when

engaged in intelligence activities. The name would help explain the enigmatic

dedication to Shake-speares Sonnets.

Assuming that the one space in the dedication was a code that meant no space, while

dots meant spaces, one could find a hidden message that Mr. W. Hall was the

begetter or author of the Sonnets.2 The dedication begins:

TO.THE.ONLIE.BEGETTER.OF.

THESE.INSVING.SONNETS.

Mr.W.H. ALL.HAPPINESSE.

Peter Farey listed these occurrences and wondered whether William Hall might have been a cover name for Christopher Marlowe. He added that he had not confirmed the information in the Phillips and Keatman book.

THESE.INSVING.SONNETS.

Mr.W.H. ALL.HAPPINESSE.

Peter Farey listed these occurrences and wondered whether William Hall might have been a cover name for Christopher Marlowe. He added that he had not confirmed the information in the Phillips and Keatman book.

I attempted to make the confirmation. I was already

suspicious because Phillips and Keatman claimed that the inverted dot/space

cipher was described in a 1608 published pamphlet by Thomas Hariot. In fact,

Hariot published only one work, in 1585. Phillips and Keatman listed their

sources for William Hall as: Historical

Manuscripts Commission (HMC) Cecil 4; State Papers (SP) Hamburg III; Public

Records Office (PRO) SP 106/2; and HMC Cecil 20. Oddly, they did not list as sources

the Canterbury Archives and Chamber Treasurer accounts which they seemed to cite.

At the Folger Shakespeare Library, I checked the Cecil

Papers both via the Calendar of the Manuscripts of the Most Hon. The Marquis of

Salisbury Preserved at Hatfield House and via the Cecil Papers electronic

database now available online from ProQuest. I looked for any occurrences of

William or W. Hall with various spellings and abbreviations from 1580-1620

which could in any way be interpreted as related to intelligence activities. I

also checked the Public Records Office Calendar of State Papers, Domestic,

1580-1610, and List and Analysis of State Papers Foreign, only available for 1589-1596.

I did not have access to SP Hamburg III.

I found none of the instances that Phillips and Keatman

cited. The best I could come up with in terms of an interesting reference to

“Hall” was a note by Sir Robert Sidney to the Earl of Essex dated Sept. 24,

1596, Flushing, stating this his letter was so short because he “found this

bearer, Mr. Hall, ready to start” (HMC Cecil Part VI, p. 398). But this gives

us no first name, nor can we tell whether Mr. Hall was employed by Sidney or

Essex, or merely someone willing to carry a letter.

Graham Phillips, sometimes writing with Keatman, penned

thirteen books investigating historical mysteries, including The Virgin Mary Conspiracy, Alexander the Great: Murder in Babylon,

and The Templars and the Ark of the

Covenant. With such a prodigious output on a wide variety of subjects, it

would not be surprising to find that some information provided in The Shakespeare Conspiracy was incorrect.

I attempted to contact Phillips through his website, but the email address

posted is no longer valid. We should, of course, continue to search for aliases

employed by Christopher Marlowe, but at this point I am skeptical that “William

Hall” was one of them.

© Donna N. Murphy, March 2015

1Phillips, Graham and Martin Keatman. The Shakespeare Conspiracy. London: Random House, 1994. 158-173; 180-181; 215.

2 Sidney Lee proposed that printer William Hall, who was apprenticed to John Allde in 1577-1584, was "W.H." for the same reason. See Robert Fleissner's Shakespeare and the Matter of the Crux: Textual, Topical, Onomastic, Authorial, and Other Puzzlements (Lewistown, PA: Mellen Press, 1991), 67-100; 243-247.

1Phillips, Graham and Martin Keatman. The Shakespeare Conspiracy. London: Random House, 1994. 158-173; 180-181; 215.

2 Sidney Lee proposed that printer William Hall, who was apprenticed to John Allde in 1577-1584, was "W.H." for the same reason. See Robert Fleissner's Shakespeare and the Matter of the Crux: Textual, Topical, Onomastic, Authorial, and Other Puzzlements (Lewistown, PA: Mellen Press, 1991), 67-100; 243-247.

Sunday, February 8, 2015

“I live to die, I die to live” by Ros Barber

On Bastian Conrad’s English language Marlowe pages, I was interested to find a new claim for Marlovian theory that I hadn’t encountered before. From 1602, the title pages of several editions of Venus and Adonis were decorated with an illustration showing a human skull with wings, balanced on the globe of the Earth, and above it an open book containing the words (in modern spelling) “I live to die, I die to live”.

Under

Marlovian theory, Christopher Marlowe faked his death in May 1593 in order to

escape being executed for atheism and heresy, and Venus and Adonis was his first publication under the name William

Shakespeare, so “I live to die, I die to live” might seem a very suitable motto

to place upon it.

Nevertheless

it is vitally important that all researchers seek to disprove their theories,

especially when it comes to theories relating to the authorship question, for

you can be quite sure that if you

don’t attempt to disprove your theory, somebody else will, and thereby cast

doubt on the quality of your pronouncements more generally.

Modern

research tools such as Early English

Books Online make it possible to do this rather easily, if one has access

to them. On examining every digitized title

page for Venus and Adonis that is available, it was

clear that this image was introduced in 1602 by the publisher William

Leake.

A

1599 edition of Venus and Adonis

printed “by R.Bradocke for William Leake, dwelling in Paule’s churchyard at the

signe of the greyhound” did not utilize this image. But William Leake’s 1602 edition, and those

he published subsequently, depicted the winged skull and the open book with its

motto. The reason becomes obvious almost

immediately. William Leake had moved

premises and was now to be found, according to the title page, “dwelling at the

sign of the Holy Ghost, in Paules Churchyard”.

The winged skull was the sign of the Holy Ghost, and “I live to die, I

die to live” was the Holy Ghost’s message of everlasting life.

A

survey of other William Leake publications confirms this; for a decade from

1602, nearly all of his publications bear this image (complete with “I live to

die, I die to live”) on their title pages including:

• John

Jewel’s Sermons (1603)

• John

Lyly’s Euphues and His England (1605)

• Henry

Smith’s Sermons (1605)

• Robert

Linaker’s A Comfortable Treatise

(1607)

• Leonard

Wright’s A Pilgrimage to Paradise

(1608)

Presumably, no one is going to argue that these writers, too, faked their deaths to avoid being killed.

In

1613, Leake changed his device to a wordless, blazing book. But it’s clear that

from 1602 to 1612, the winged skull with its motto that decorated Venus and Adonis – and many other books

besides – was simply a marker of the William Leake brand.

© Ros Barber, February 2015

Tuesday, January 27, 2015

Ros Barber Wins Hoffman Prize

Congratulations to our great friend, Dr. Rosalind Barber, for co-winning the 2014 Hoffman Prize for her paper entitled “‘Shortly he will quite forget to go’: Marlowe and the

Faustus Epigrams.” The prize is awarded by the King's School for a "distinguished publication on Christopher Marlowe."

Congratulations, Ros!

This

is Ros’s second Hoffman. She won the

prize in 2011 for her debut novel, The Marlowe Papers.

Congratulations, Ros!

Sunday, December 21, 2014

Rethinking the Sonnets: Ros Barber's Groundbreaking Article on Marlovian Perspective Now Available

Click here to read the first article exploring a "Marlovian"

perspective on Shakespeare's Sonnets to be published in a peer-reviewed

history journal: Rethinking History (June 2010). Ros Barber's "Exploring Biographical Fictions: the Role of Imagination in Writing and Reading Narrative" is now free to read on open access.

Thursday, September 18, 2014

Stylometrics and Edward II by Peter Farey

One piece of

stylometric evidence which seems at first sight to throw quite a large spanner

into the Marlovian works appears in Shakespeare,

Computers, and the Mystery of Authorship, edited by Hugh Craig and Arthur

F. Kinney.1 The book itself is not concerned with the Shakespeare

authorship question as such, but with whether certain parts of Shakespeare's

works or apocrypha are either by him or by a collaborator. For example, Craig

argues quite convincingly for Marlowe having made significant contributions to

parts one and two of Shakespeare's Henry

VI trilogy.

It is in a chapter called 'The authorship of The Raigne of Edward the Third' (by Timothy Irish West), however, that the item having most significance for the Marlovian theory appears. It is a chart (Fig.6.8, p.130) in which he is simply testing the validity of an approach being used to see whether Shakespeare wrote either the 'Countess' scenes (I.ii–II.ii) or the 'French campaign' scenes (III.i–IV.iii) in Edward III.

In this graph there are 90 shaded circles representing segments of 6000 words each from 27 plays which are taken to be solely by Shakespeare. There are also 236 diamond shapes representing 6000-word segments from 85 other single-author plays written between 1580 and 1619.

The horizontal (X) axis represents the extent to which each segment includes lexical words2 which have been identified as more characteristic of Shakespeare's works than the others'. The vertical (Y) axis shows the extent to which it uses words more typical of the others' works than Shakespeare's.3 Not surprisingly, they divide into two fairly distinct clusters – the circles in one and the diamonds in another.

In this particular chart, West has removed the three 6000-word segments of Marlowe's Edward II from the data, and treated them as if it were all of unknown authorship. Shown as black triangles on the chart, all three fall quite clearly within the 'other authors' cluster, and not within the 'Shakespeare' one. Here is the result. (The caption should of course read 'segments of Edward II', not 'segments of Edward III'.)

Against this, he shows (pp.127–8) segments from Shakespeare's King John, Henry IV (part 1) and Henry V, all of which fall in the 'Shakespeare' cluster, albeit at the edge nearest to the other one.

There is no doubt that this is a fairly strong piece of evidence that the author of Edward II (i.e. Marlowe) was not also the author of the Shakespeare canon. A few points need to be borne in mind, however, before we all admit defeat.

1. Although the data for Edward II are ignored in arriving at the characteristic words for the 'other authors', all of the rest of Marlowe's plays (except Dido, because of the possible input by Thomas Nashe) are included, whereas they would all need to be ignored too if the intention was to assess Marlowe as a Shakespeare authorship candidate – which it wasn't.

2. The three Henry VI plays, Titus Andronicus and The Taming of the Shrew – those which because of time proximity are most likely to have similarities to Marlowe – play no part in this calculation.

3. This also means that there is no play in the 'Shakespeare' set which is known to have been written less than five years or so after Edward II.

4. Furthermore, the Shakespeare set includes plays as late as The Tempest, written some twenty years later.

This question of date is of crucial importance in any stylometric attempt to assign authorship. Let me give an example which is in essence a very much simplified version of the method employed by Craig and Kinney (and West).

Suppose that there are two bodies of work, one which we will ascribe to playwright A and the other playwright B.

We work out that the frequency with which they each use the words 'most' and 'then' differs greatly. In fact, if we add up the total for both words in a play by either of them and find what percentage of them are 'most' we can be fairly sure that:

1Craig, Hugh; Kinney, Arthur F. (2009). Shakespeare, Computers, and the Mystery of Authorship. Cambridge University Press.

2According to Craig & Kinney (p.224), "Words can be classified into functional words and lexical words (with just a few doubtful cases). Function words have a grammatical function; examples are the, and, she, before, and of. [...] Lexical words [are] nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs which can be substituted for each other in a given sentence." They give king and mother as examples.

3The most characteristic words for Shakespeare (the horizontal axis) are found by calculating the proportion of 'Shakespeare' segments within which a given word appears and adding this to the proportion of 'others' segments within which it does not appear (giving a theoretical maximum of +2). The 500 words with the highest scores are the ones used. For the vertical axis, the same procedure is followed, but finding those words with the highest combination of proportions 'within the others' and 'not within Shakespeare'.

It is in a chapter called 'The authorship of The Raigne of Edward the Third' (by Timothy Irish West), however, that the item having most significance for the Marlovian theory appears. It is a chart (Fig.6.8, p.130) in which he is simply testing the validity of an approach being used to see whether Shakespeare wrote either the 'Countess' scenes (I.ii–II.ii) or the 'French campaign' scenes (III.i–IV.iii) in Edward III.

In this graph there are 90 shaded circles representing segments of 6000 words each from 27 plays which are taken to be solely by Shakespeare. There are also 236 diamond shapes representing 6000-word segments from 85 other single-author plays written between 1580 and 1619.

The horizontal (X) axis represents the extent to which each segment includes lexical words2 which have been identified as more characteristic of Shakespeare's works than the others'. The vertical (Y) axis shows the extent to which it uses words more typical of the others' works than Shakespeare's.3 Not surprisingly, they divide into two fairly distinct clusters – the circles in one and the diamonds in another.

In this particular chart, West has removed the three 6000-word segments of Marlowe's Edward II from the data, and treated them as if it were all of unknown authorship. Shown as black triangles on the chart, all three fall quite clearly within the 'other authors' cluster, and not within the 'Shakespeare' one. Here is the result. (The caption should of course read 'segments of Edward II', not 'segments of Edward III'.)

Against this, he shows (pp.127–8) segments from Shakespeare's King John, Henry IV (part 1) and Henry V, all of which fall in the 'Shakespeare' cluster, albeit at the edge nearest to the other one.

There is no doubt that this is a fairly strong piece of evidence that the author of Edward II (i.e. Marlowe) was not also the author of the Shakespeare canon. A few points need to be borne in mind, however, before we all admit defeat.

1. Although the data for Edward II are ignored in arriving at the characteristic words for the 'other authors', all of the rest of Marlowe's plays (except Dido, because of the possible input by Thomas Nashe) are included, whereas they would all need to be ignored too if the intention was to assess Marlowe as a Shakespeare authorship candidate – which it wasn't.

2. The three Henry VI plays, Titus Andronicus and The Taming of the Shrew – those which because of time proximity are most likely to have similarities to Marlowe – play no part in this calculation.

3. This also means that there is no play in the 'Shakespeare' set which is known to have been written less than five years or so after Edward II.

4. Furthermore, the Shakespeare set includes plays as late as The Tempest, written some twenty years later.

This question of date is of crucial importance in any stylometric attempt to assign authorship. Let me give an example which is in essence a very much simplified version of the method employed by Craig and Kinney (and West).

Suppose that there are two bodies of work, one which we will ascribe to playwright A and the other playwright B.

We work out that the frequency with which they each use the words 'most' and 'then' differs greatly. In fact, if we add up the total for both words in a play by either of them and find what percentage of them are 'most' we can be fairly sure that:

* if it's

less than 40%, it's by playwright A

* if it's

more than 40%, it's by playwright B

(In fact

this works for all of A's 21 plays bar one, and all of B's 16 except two. You

would need to get a bit more complicated to get 100% in each case!)

Now let’s

imagine that we have a play where we suspect collaboration between the two

playwrights. We find that Acts 1 & 2 are well below 40% (so probably

playwright A) and Acts 3 & 5 well above (playwright B). Act 4 is more

doubtful at 43%.

So does this tell us anything at all about whether the two playwrights are different people? No. In fact playwright A is Shakespeare before 1600, and playwright B is Shakespeare after 1600. And Twelfth Night (1601?) was the play in question, if you were wondering.

What we can see, therefore, is that to claim that this tells us they were different people is circular reasoning. If you start with an assumption that they are two different people, and take no account of time, then it’s hardly surprising that this is just what the figures will seem to show.

Don't get me wrong, though. This is a powerful piece of evidence against the Marlovian theory, and it would be wrong to think otherwise.

So does this tell us anything at all about whether the two playwrights are different people? No. In fact playwright A is Shakespeare before 1600, and playwright B is Shakespeare after 1600. And Twelfth Night (1601?) was the play in question, if you were wondering.

What we can see, therefore, is that to claim that this tells us they were different people is circular reasoning. If you start with an assumption that they are two different people, and take no account of time, then it’s hardly surprising that this is just what the figures will seem to show.

Don't get me wrong, though. This is a powerful piece of evidence against the Marlovian theory, and it would be wrong to think otherwise.

© Peter

Farey, September 2014

1Craig, Hugh; Kinney, Arthur F. (2009). Shakespeare, Computers, and the Mystery of Authorship. Cambridge University Press.

2According to Craig & Kinney (p.224), "Words can be classified into functional words and lexical words (with just a few doubtful cases). Function words have a grammatical function; examples are the, and, she, before, and of. [...] Lexical words [are] nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs which can be substituted for each other in a given sentence." They give king and mother as examples.

3The most characteristic words for Shakespeare (the horizontal axis) are found by calculating the proportion of 'Shakespeare' segments within which a given word appears and adding this to the proportion of 'others' segments within which it does not appear (giving a theoretical maximum of +2). The 500 words with the highest scores are the ones used. For the vertical axis, the same procedure is followed, but finding those words with the highest combination of proportions 'within the others' and 'not within Shakespeare'.

Monday, June 23, 2014

Is the Corpus Christi Portrait Marlowe?

Click here to read The Marlowe Society's post on the June 23 Times (U.K.) article concerning doubts about Marlowe being the sitter of the famous Corpus Christi portrait. Click here for Ros Barber's June 25 letter to the Times regarding this matter (via our International Marlowe-Shakespeare Society Facebook page).

Sunday, June 15, 2014

Worth Repeating: On the Shakespeare "Front"

A recent exchange on the "Oxfraud" Facebook page (commencing June 6), which consists of comments by International Marlowe-Shakespeare Society members Peter Farey and Daryl Pinksen, has prompted this blog to re-post two older blog articles on the issue of Shakespeare being a front for another, possibly blacklisted writer. In "Philip Yordan: A Modern-Day Shakespeare?" Daryl Pinksen examines some compelling parallels between Marlowe and the Hollywood blacklisting of the 1950s. In "William Shakespeare, Businessman - Forgotten Genius," Anthony Kellett also explores the life of a literary front man. We welcome your comments to these provocative pieces.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)